The Iconic NYC Architect Who Transformed The City Skyline With Polycor Stone

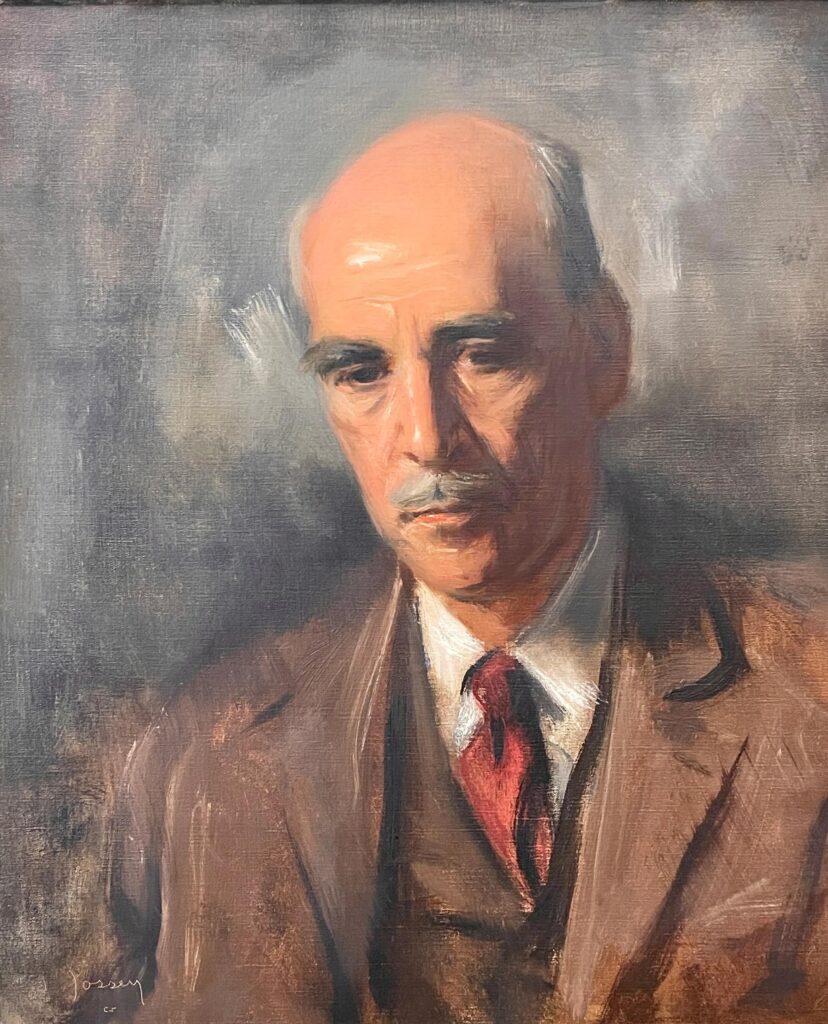

The term “starchitect” has come to describe a small class of architects whose work is so extraordinary that they become famous among everyday people. Had it existed in the time of William F. Lamb, he would have bristled at the label.

Lamb knew the opening of his most famous project, the Empire State Building, would mean a day of speeches, flashing camera bulbs, and shaking hands with politicians and wealthy financiers. So when he found out the date, he booked a cruise to Europe to make sure he wouldn’t be there.

“He did not like public speeches or public encomiums or anything like that,” his wife recalled. “We sailed just an hour or two before the party began. And the captain of the Île de France invited us up to his quarters, to have a drink, and to listen to the party [on the radio]. And Bill was in a state of absolute delight. The job was done, and well done, and he said, ‘Isn’t this marvelous? We don’t have to listen to all these speeches!’”

Arguably no architect has done as much to shape New York City’s skyline as Lamb. Through the Roaring 20s and the Great Depression, Lamb, a partner in the firm of Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, designed a succession of buildings that are today regarded as Art Deco masterworks.

Some of their signature design elements were accomplished with natural stone from iconic American quarries that are now owned by Polycor. While many of the exteriors of modern day towers in Manhattan are made of gleaming glass and metal, the buildings of the first half of the 20th century were clad in timeless materials like limestone, granite and marble.

The stone imparted a sense of grandeur and made structures less vulnerable to the fires and elements that destroyed buildings from New York’s historic past. The cladding had a longer lifecycle and could better withstand the elements, making for a more sustainable building. A term that wouldn’t be used until a half-century later in 1987 in the Brundtland Report (also known as ‘Our Common Future’) produced for the UN.

A true New York native, Lamb was born in Brooklyn in 1883 and died in the city in 1952. Take a tour below of some of the landmarks he designed in his mighty hometown with contributions from Polycor stone.

The Empire State Building

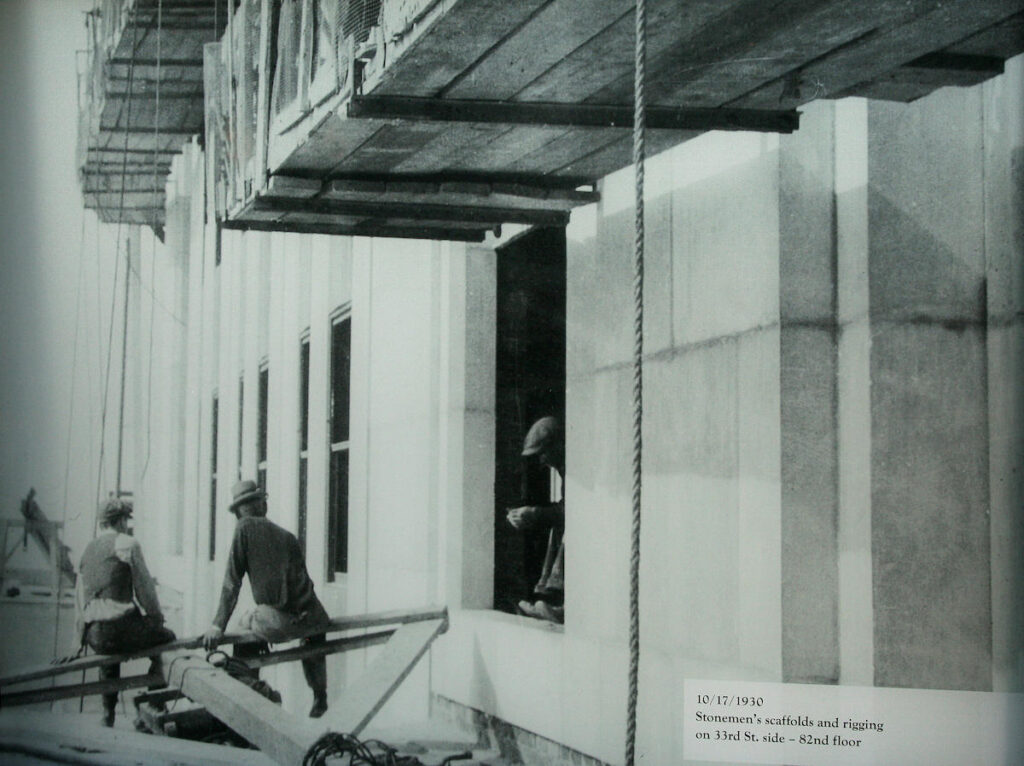

Quite simply, the most famous skyscraper in the world. Lamb drafted the original Empire State Building design in two weeks, and at the urging of investors, upwardly revised it a handful of times to ensure it stayed ahead of the Chrysler Building, then under construction, as the tallest in the world.

At 102 stories and 1,454 feet to the top of its spire, it held that position for four decades. The building was clad in 200,000 cubic feet of Indiana Limestone from the aptly named Empire quarry in Oolitic, Indiana, giving it its signature buff color. Incredibly, the entire building was constructed and open to tenants just 20 months from the time Lamb first sat down to work on its design.

“I sketched the design of the Empire State Building in just two weeks.” – William F. Lamb

It has stood the test of time, weathering countless storms and enduring the wear and tear of millions of visitors. But perhaps the most impressive testament to the building’s structural integrity came at the end of World War II, when a U.S. Army Air Force B-25 bomber crashed into the building on a foggy morning in 1945.

Despite the tragic loss of life both in the building and on the ground, the Empire State Building itself sustained only minor damage that was quickly repaired. It was a testament to Lamb’s design and the building’s construction that it survived such a deadly incident with only superficial wounds.

Bankers Trust Company Building

Located at 14 Wall Street, the Bankers Trust Company Building originally consisted of a 32-story tower capped with a pyramid modeled after the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. But business was good for the J.P. Morgan-associated company, and less than two decades after opening, Bankers Trust commissioned Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, to design a major addition.

The Lamb-designed annex was constructed in place of three smaller neighboring buildings and attached to the tower to form an L-shape. The annex peaked at 25 stories so the original tower would retain its prominence. The Art Deco building’s facade was made of Woodbury Gray granite.

Standard Oil Building

In 1885, John D. Rockefeller moved Standard Oil’s headquarters from Cleveland to 26 Broadway in the heart of New York’s Financial District (the address was once said to belong to Alexander Hamilton). The original building stood only 10 stories but underwent a series of additions that reflected the company’s growing economic might.

In 1920, architect Thomas Hastings of Carrère and Hastings began work on the building that visitors see today, with Lamb and his firm serving as consulting architects. The building is known for the unique curvature of its lower portion, which parallels Broadway at that stretch of road.

A number of setbacks in its upper portions, along with rotations to its axis, give the appearance more of a cluster of separate buildings instead of one. With its Indiana Limestone façade and illuminated pyramid at the top of its tower, the Standard Oil Building projected its influence far and wide to passersby on the street and even as far as the ships entering New York Harbor.

40 Wall Street

40 Wall Street, known at various times as the Manhattan Trust Building, the Bank of Manhattan Company Building, and today the Trump Building, was designed by lead architect H. Craig Severance, Yasuo Matsui as associate architect, and Lamb’s firm as consulting architect. The building held the title of the world’s tallest building for one month in 1930.

The 927-foot tower was redesigned multiple times to stay ahead of the Chrysler Building, under construction simultaneously in Midtown. But in the competition the media dubbed “the race to the skies,” the Chrysler Building’s designers had a 185-foot trick up their sleeve.

The Chrysler building’s iconic spire was secretly constructed within its upper floors, then raised up and placed like a crown at its top only at the very end. The 40 Wall Street architectural team was up in arms and made a case to the press that theirs was the true tallest building since its 70 floors of inhabitable space were higher. Of course, Lamb had the last laugh, soundly winning the race a year later in 1931 with the Empire State Building’s completion.

Although regarded as an Art Deco building, 40 Wall Street is known for features that deviate from that style, including a turquoise neo-Gothic pyramid at its top and Indiana Limestone colonnades on its first five floors, designed to blend with the Neoclassic architecture of neighboring Federal Hall.

The Reynolds Building

Although this building isn’t in New York, it plays an important role in this story. Take a quick glance at it – look familiar? The 22-floor Reynolds Building, designed by Lamb’s firm, served as the architectural inspiration (or mock-up, if you will) for the Empire State Building.

The Art Deco skyscraper was completed in 1929 in downtown Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to serve as the headquarters of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. In a nod to their family resemblance, the Reynolds Building received a card from the Empire State Building’s general manager in 1979 reading, “HAPPY ANNIVERSARY, DAD.” Like it’s New York counterpart, the Reynolds Building was clad in Indiana limestone from the same Polycor quarries.

Want to build your project with the same materials as these American icons? Click here to visit the Polycor Resources page and download our 3-part spec sheets to get started on developing your spec for your project. See these and more projects by William F. Lamb in our Projects gallery.